Toddsterpatriot

Diamond Member

Ya, what a load.

First, before healthcare and health insurance came about people faced early death and financial ruin from bad medical event.

Second, college costs have increased as state governments decreased funding for them. For example in 1982 WI financed 50% of the UW system while today just 17%.

Also, both hospitals and colleges compete for excellence by offered better care or education which doesn’t mean cutting the product.

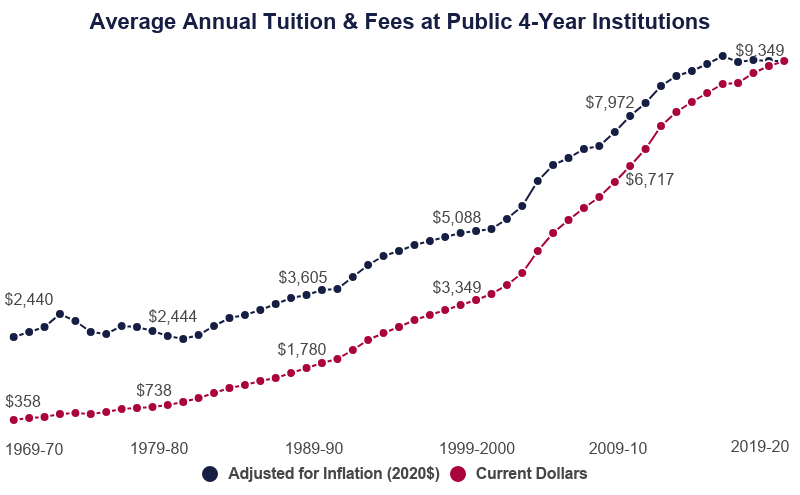

Second, college costs have increased as state governments decreased funding for them.

Costs have increased despite unlimited piles of federal money?