Sixties Fan

Diamond Member

- Mar 6, 2017

- 58,742

- 11,130

- 2,140

- Thread starter

- #481

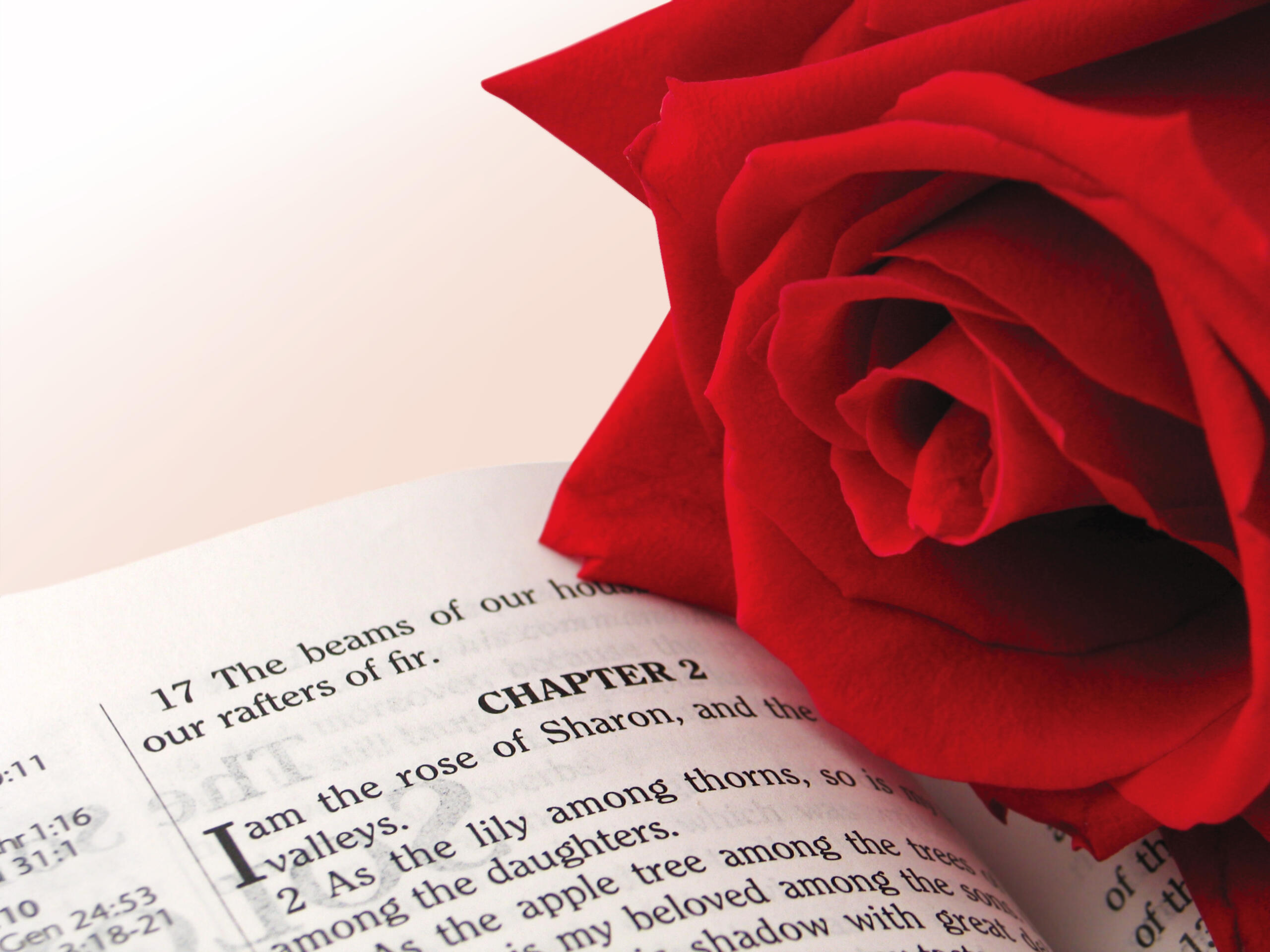

Roman Abramovich’s tangled Portuguese roots

Documents filed in his citizenship case show the validity of his claims and reveal the complexity of Sephardic heritage