NewsVine_Mariyam

Platinum Member

As I was reading this story, several things crossed my mind. While I don't live in Cummings, Georgia, the refrain from this narrative is universal as it applies to the lives of Black Americans.

A woman is assaulted (a white woman) and then later dies of her injuries and the only three Black people in that area of Forsyth County at that time were accused of the crime. Based on a confession that is alleged to have been coerced, the 24 year old was arrested and jailed. Soon thereafter an angry white mob dragged him from his jail cell where he was riddled with bullets and beaten with a crowbar. I'm not sure how he was still alive after all of that but he was then "hitched onto the back of a wagon with a noose around his neck and eventually hanged in the Cumming town square" where people took turns throwing stones at him and shooting more bullets into his dead body while the mob cheered. The other two Black residents who were teenagers were later lynched after one-day expediated trials that precipitated the onslaught of racial violence and terror aimed at the county's Black residents, including the Ku Klux Klan Night Riders visiting terror upon them until they had driver every single Black person not just from Cummings, but all of Forsyth County. Forsyth remained all white for the next 75 years.

Emmitt Til, a 14 year old, who was kidnapped, and murdered by lynching for allegedly whistling at a white woman was one of the historical events that came to mind while I read this. The article also brought to mind the Tulsa race riot in the which the most affluent Black community in the country was torched, and bombed out of existence. On that case like this one, none of the Black business owners or residents were compensated for thier losses, with the insurance companies denying each and every single claims. The mob also robbed the Black banks and whoever the guarantors were at that time, refused to honor any of these claims as well.

While of all this is beyond horrendous, the insult to the injury however is that out of a mob of 3,000 people in Tulsa, and however many were participants in the Forsyth lynchings, not a single white person was ever arrested, let alone charged or made accountable for the crimes they committed and the harm they had inflicted. In the case of Emmitt Til he was murdered because a white woman sent someone after him, they admitted they did it, that she initiated it yet none of them have been held accountable.

If a person or entity has done something that has caused harm, no healing can occur if the entity or person keeps insisting that nothing occurred. That's where confronting the past comes in.

Is this possible? To confront the past so that we all can move on to a better future?

Prohibited:

Lisa558

jwoodie

Concerned American

Indeependent

Lastamender

mudwhistle

ozro

Leo123

A woman is assaulted (a white woman) and then later dies of her injuries and the only three Black people in that area of Forsyth County at that time were accused of the crime. Based on a confession that is alleged to have been coerced, the 24 year old was arrested and jailed. Soon thereafter an angry white mob dragged him from his jail cell where he was riddled with bullets and beaten with a crowbar. I'm not sure how he was still alive after all of that but he was then "hitched onto the back of a wagon with a noose around his neck and eventually hanged in the Cumming town square" where people took turns throwing stones at him and shooting more bullets into his dead body while the mob cheered. The other two Black residents who were teenagers were later lynched after one-day expediated trials that precipitated the onslaught of racial violence and terror aimed at the county's Black residents, including the Ku Klux Klan Night Riders visiting terror upon them until they had driver every single Black person not just from Cummings, but all of Forsyth County. Forsyth remained all white for the next 75 years.

Emmitt Til, a 14 year old, who was kidnapped, and murdered by lynching for allegedly whistling at a white woman was one of the historical events that came to mind while I read this. The article also brought to mind the Tulsa race riot in the which the most affluent Black community in the country was torched, and bombed out of existence. On that case like this one, none of the Black business owners or residents were compensated for thier losses, with the insurance companies denying each and every single claims. The mob also robbed the Black banks and whoever the guarantors were at that time, refused to honor any of these claims as well.

While of all this is beyond horrendous, the insult to the injury however is that out of a mob of 3,000 people in Tulsa, and however many were participants in the Forsyth lynchings, not a single white person was ever arrested, let alone charged or made accountable for the crimes they committed and the harm they had inflicted. In the case of Emmitt Til he was murdered because a white woman sent someone after him, they admitted they did it, that she initiated it yet none of them have been held accountable.

If a person or entity has done something that has caused harm, no healing can occur if the entity or person keeps insisting that nothing occurred. That's where confronting the past comes in.

Is this possible? To confront the past so that we all can move on to a better future?

Prohibited:

Lisa558

jwoodie

Concerned American

Indeependent

Lastamender

mudwhistle

ozro

Leo123

White supremacy activists picketing at a march in Forsyth County, Ga., Jan. 17, 1987. (Steve Deal/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP)CUMMING, Ga. — Driving through present-day Forsyth County is like navigating an American landscape haunted by its history. Centuries-old churches and storied cemeteries carry remnants of past lives, of a Black community vanquished by racial terror. Atop several acres of land sit 20th-century-built homes, housing generations of Forsythians.The county, located 30 miles north of Atlanta and home to about 235,000 residents, presents itself as an ideal place to live and raise a family. The affluent suburb champions its high-performing public schools, growing diverse community and promise of a better life.But beneath the surface of this vibrant community is a deep and complex history rooted in hate.While 1 in 3 residents in Forsyth County are people of color, only about 4.9% of the population is Black, a figure that’s been stagnant for four decades. This is due in large part to a massive racial cleansing that rocked the county in 1912, followed by 75 years when Black people were banned from moving back in.

White supremacy activists picketing at a march in Forsyth County, Ga., Jan. 17, 1987. (Steve Deal/Atlanta Journal-Constitution via AP)CUMMING, Ga. — Driving through present-day Forsyth County is like navigating an American landscape haunted by its history. Centuries-old churches and storied cemeteries carry remnants of past lives, of a Black community vanquished by racial terror. Atop several acres of land sit 20th-century-built homes, housing generations of Forsythians.The county, located 30 miles north of Atlanta and home to about 235,000 residents, presents itself as an ideal place to live and raise a family. The affluent suburb champions its high-performing public schools, growing diverse community and promise of a better life.But beneath the surface of this vibrant community is a deep and complex history rooted in hate.While 1 in 3 residents in Forsyth County are people of color, only about 4.9% of the population is Black, a figure that’s been stagnant for four decades. This is due in large part to a massive racial cleansing that rocked the county in 1912, followed by 75 years when Black people were banned from moving back in. Now the county is grappling with its failure to fully confront that dark past — a potential impediment to its progress. It's a failure that extends from Forsyth’s schools, where there is no established core curriculum on the events of 1912, to its residents, some of whom are content with how the county is moving forward and others who are hoping for a real reckoning.“Forsyth County is right on the borderline between Atlanta's influence and rural Georgia,” poet, author and former county resident Patrick Phillips told Yahoo News. “It's also on the border between everything we hope will change about the way the country remembers the past and then another group of people who don't want to talk about any of that.”

Now the county is grappling with its failure to fully confront that dark past — a potential impediment to its progress. It's a failure that extends from Forsyth’s schools, where there is no established core curriculum on the events of 1912, to its residents, some of whom are content with how the county is moving forward and others who are hoping for a real reckoning.“Forsyth County is right on the borderline between Atlanta's influence and rural Georgia,” poet, author and former county resident Patrick Phillips told Yahoo News. “It's also on the border between everything we hope will change about the way the country remembers the past and then another group of people who don't want to talk about any of that.”

The lynching The tombstone of Mae Crow in Forsyth County's Pleasant Grove Cemetery. Three Black men were accused in 1912 of beating, raping and killing her, with little evidence. (Marquise Francis/Yahoo News)Following Reconstruction, the 12 years after the Civil War, Forsyth County was home to about 12,000 residents, including a relatively small but growing population of Black people, dozens of whom were landowners. Newly freed Black Americans were just beginning to confront a world where opportunity and hope were possible.But in September 1912, everything changed when an 18-year-old white woman named Mae Crow was found beaten, bloodied and unconscious in the Georgia woods under mysterious circumstances. She later died from her injuries, and three young Black men — the only Black people in that part of the county at the time — were accused of raping and murdering her, with little evidence other than a coerced confession from one of them.As a result, 24-year-old Rob Edwards was arrested and jailed for the crime, and soon afterward was dragged from his cell by a mob of angry white residents. His body was riddled with bullets and beaten with crowbars, then allegedly hitched onto the back of a wagon with a noose around his neck and eventually hanged in the Cumming town square.People took turns stoning and shooting more bullets at his limp corpse as hundreds of onlookers rejoiced. Two Black teens, Ernest Knox, 16, and Oscar Daniel, 18, were later hanged after expedient one-day trials that led to an onslaught of racial violence and terror toward the county’s Black residents.

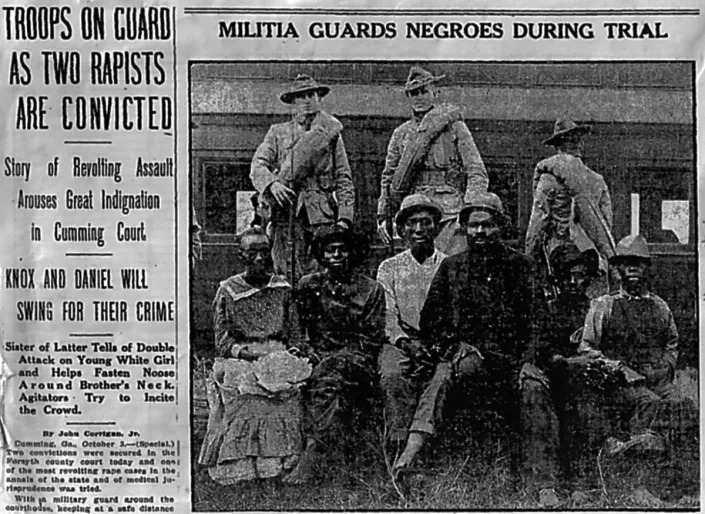

The tombstone of Mae Crow in Forsyth County's Pleasant Grove Cemetery. Three Black men were accused in 1912 of beating, raping and killing her, with little evidence. (Marquise Francis/Yahoo News)Following Reconstruction, the 12 years after the Civil War, Forsyth County was home to about 12,000 residents, including a relatively small but growing population of Black people, dozens of whom were landowners. Newly freed Black Americans were just beginning to confront a world where opportunity and hope were possible.But in September 1912, everything changed when an 18-year-old white woman named Mae Crow was found beaten, bloodied and unconscious in the Georgia woods under mysterious circumstances. She later died from her injuries, and three young Black men — the only Black people in that part of the county at the time — were accused of raping and murdering her, with little evidence other than a coerced confession from one of them.As a result, 24-year-old Rob Edwards was arrested and jailed for the crime, and soon afterward was dragged from his cell by a mob of angry white residents. His body was riddled with bullets and beaten with crowbars, then allegedly hitched onto the back of a wagon with a noose around his neck and eventually hanged in the Cumming town square.People took turns stoning and shooting more bullets at his limp corpse as hundreds of onlookers rejoiced. Two Black teens, Ernest Knox, 16, and Oscar Daniel, 18, were later hanged after expedient one-day trials that led to an onslaught of racial violence and terror toward the county’s Black residents. The people in this October 1912 newspaper photo are not identified but are believed to be, front row from left: Trussie (Jane) Daniel, Oscar Daniel, Tony Howell (defendant in another rape case involving a white woman), Ed Collins (witness), Isaiah Pirkle (witness for Howell) and Ernest Knox. (Atlanta Constitution)By the year’s end, all of the county’s 1,098 Black residents — or 10% of the population — were violently forced out as Black churches were set ablaze, threatening fliers made by white vigilantes were circulated and night riders made life torture for anyone in the community who was not white, particularly its Black sharecroppers and business owners.Many Black residents who owned homes were unable to sell their properties in enough time, devastating entire families. And in many ways, Black life in the county has never fully recovered.“I cannot imagine what it must have felt like to have night riders coming through these Black neighborhoods and burning people's houses and forcing them out,” 71-year-old Elon Osby told Yahoo News. Osby, whose grandparents William and Ida Bagley owned over 60 acres of land in Forsyth in 1912 before having to leave it all behind, added: “The fear is unimaginable. But then to leave your land with no opportunity to be compensated for it, that's the next unimaginable thing.”Today, Osby says, several half-million-dollar subdivision homes sit on the land her grandparents once owned. The family never received anything for it.A newspaper headline in the Atlanta Constitution around that time read: “Negroes Flee From Forsyth: Enraged White People Are Driving Blacks From County.”The county remained all white for more than seven decades after the 1912 expulsion, with comprehensive details about the systematic removal of Black residents buried in old articles and history books for decades.

The people in this October 1912 newspaper photo are not identified but are believed to be, front row from left: Trussie (Jane) Daniel, Oscar Daniel, Tony Howell (defendant in another rape case involving a white woman), Ed Collins (witness), Isaiah Pirkle (witness for Howell) and Ernest Knox. (Atlanta Constitution)By the year’s end, all of the county’s 1,098 Black residents — or 10% of the population — were violently forced out as Black churches were set ablaze, threatening fliers made by white vigilantes were circulated and night riders made life torture for anyone in the community who was not white, particularly its Black sharecroppers and business owners.Many Black residents who owned homes were unable to sell their properties in enough time, devastating entire families. And in many ways, Black life in the county has never fully recovered.“I cannot imagine what it must have felt like to have night riders coming through these Black neighborhoods and burning people's houses and forcing them out,” 71-year-old Elon Osby told Yahoo News. Osby, whose grandparents William and Ida Bagley owned over 60 acres of land in Forsyth in 1912 before having to leave it all behind, added: “The fear is unimaginable. But then to leave your land with no opportunity to be compensated for it, that's the next unimaginable thing.”Today, Osby says, several half-million-dollar subdivision homes sit on the land her grandparents once owned. The family never received anything for it.A newspaper headline in the Atlanta Constitution around that time read: “Negroes Flee From Forsyth: Enraged White People Are Driving Blacks From County.”The county remained all white for more than seven decades after the 1912 expulsion, with comprehensive details about the systematic removal of Black residents buried in old articles and history books for decades.