Sixties Fan

Diamond Member

- Mar 6, 2017

- 58,432

- 11,063

- 2,140

- Thread starter

- #21

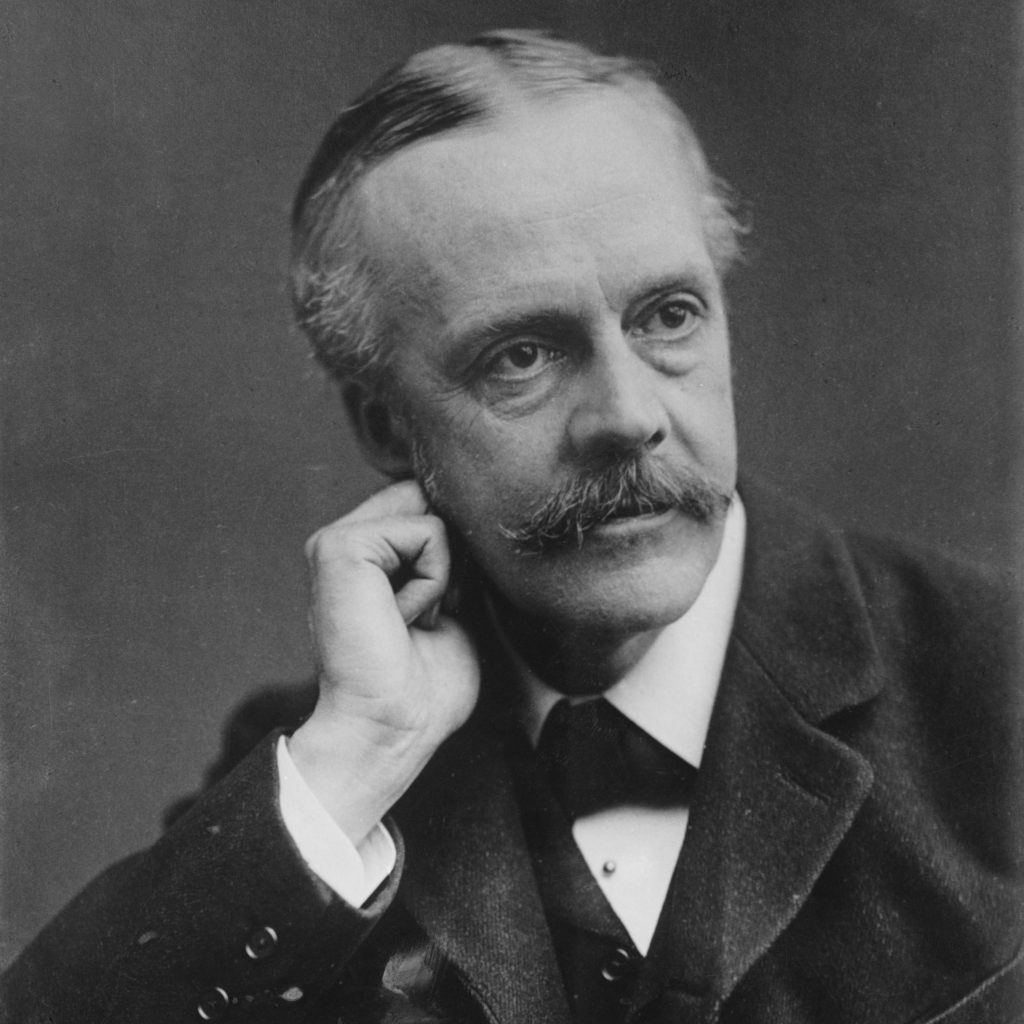

The Mufti’s Long-Lasting Legacy

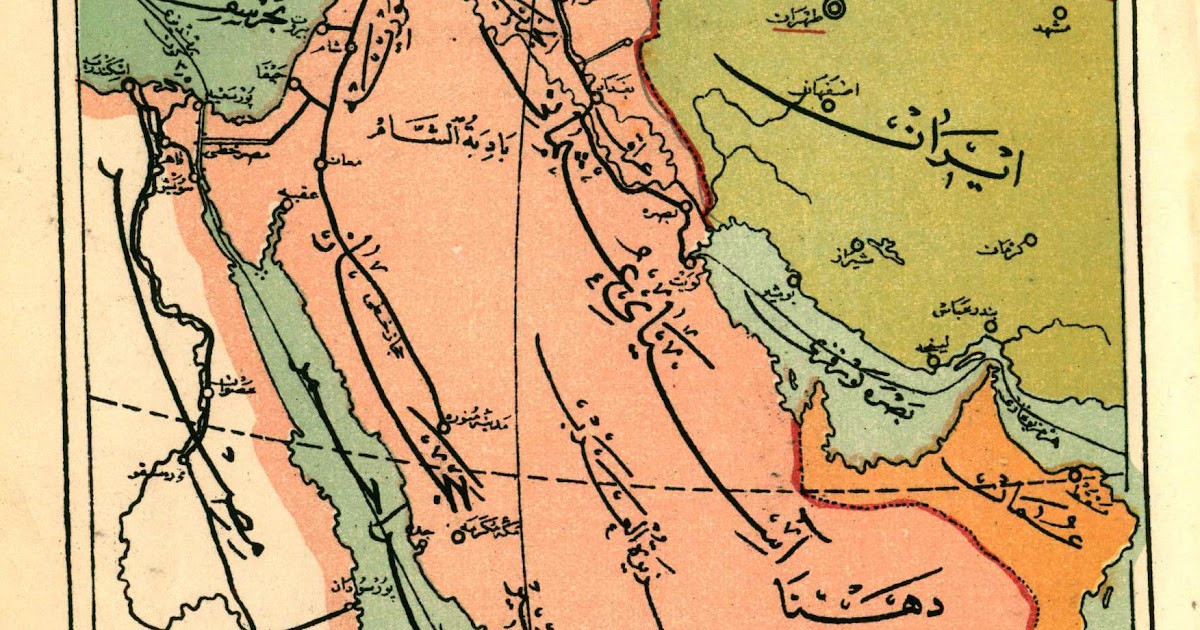

From that time to the present, Islamists have asserted that the religion of Islam is an inherently anti-Jewish religion and that this hatred of Judaism and the Jews has everything to do with the classic texts of the Koran and the Hadith.55 As we have seen, in light of the Bludan text, Husseini brought these convictions with him to Berlin in 1941. These beliefs and an uncompromising opposition both to the Allied coalition as well as to Zionism constitute part of the foundation for his collaboration with Hitler. As the archives of the Nazi regime made very clear, not only Hitler, but also officials in the German Foreign Office, the Propaganda Ministry, the SS officials in the Reich Security Main Office and the German military intelligence officers fighting in North Africa were pleased to learn that there was an indigenous form of Islamic, that is, a non-Christian, non-European tradition of hatred of the Jews with apparent theological foundations. For Husseini and the Islamists of the 1930s and 1940s, the secular political battle against Zionism was inseparable from the religious battle against the Jews. Starting from very different cultural and ideological first premises, anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism converged at the same time in Bludan, Syria and in Nazi Berlin. Hitler, Himmler and others in the Nazi regime displayed an admiration for what they understood Islam to be, namely a warrior religion, in contrast to pacifist currents in Christianity, and one that shared their animus against their Jews.56Following World War II, Husseini received a hero’s welcome in Egypt and Palestine, In 1946, Hassan al-Banna (1906-1949), founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, called Husseini a “hero who challenged an empire and fought Zionism with the help of Hitler and Germany. Germany and Hitler are gone, but Amin Al-Husseini will continue the struggle.”57 It was Husseini’s experience fighting the British and his collaboration with Nazism that al-Banna and his fellow members of the Muslim Brotherhood found so inspiring. So did the members of the Arab Higher Committee and the Palestine People’s Party that chose Husseini as their leader in 1945.58 Following the Arab-Palestinian defeat of 1948, Husseini’s political fortunes declined, yet he remained a revered figure in parts of Arab and Palestinian societies. The evidence of his collaboration with the Nazis was either forgotten, ignored or excused as a form of justified anti-colonialism in an alliance of convenience, not shared ideological passion, against a common enemy.

To repeat, the historical importance of Haj Amin al-Husseini did not consist his contribution to the decision to carry out the Holocaust in Europe. Rather it lay in his collaboration with Nazi Germany’s unsuccessful effort to win the war in North Africa and the Middle East and to extend the Holocaust to the Jews of the region. By doing so, he created his most important and longest lasting legacy. It was both by creating some of the canonical texts of the Islamist tradition and in combining elements of European and Islamist Jew-hatred. He thus founded a tradition of absolute and uncompromising rejection of Zionism and later, of the State of Israel. The impact of Husseini the ideologue is as important and as destructive as Husseini the political figure. His own texts before and during the crucial years of exile in Nazi Berlin reveal the real Husseini, the unifier of an extremist but influential interpretation of Islam and its founding texts with the modern secular language of anti-imperialism and anti-Zionism. His target, first and foremost, was the Jews of North Africa and the Middle East, and subsequently, the State of Israel. They were the objects of his greatest hatred and of his considerable political energy. Husseini played a vital role in spreading the falsehood that a Jewish state would be determined somehow to threaten the Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Nazis and the Holocaust

From 1941 to 1945, al-Husseini played a central role in shaping the political tradition of Islamism. - Jeffrey Herf - JPSR - Jerusalem Center

jcpa.org

jcpa.org