Stuartbirdan2

Diamond Member

- Sep 6, 2020

- 1,220

- 9,187

- 2,138

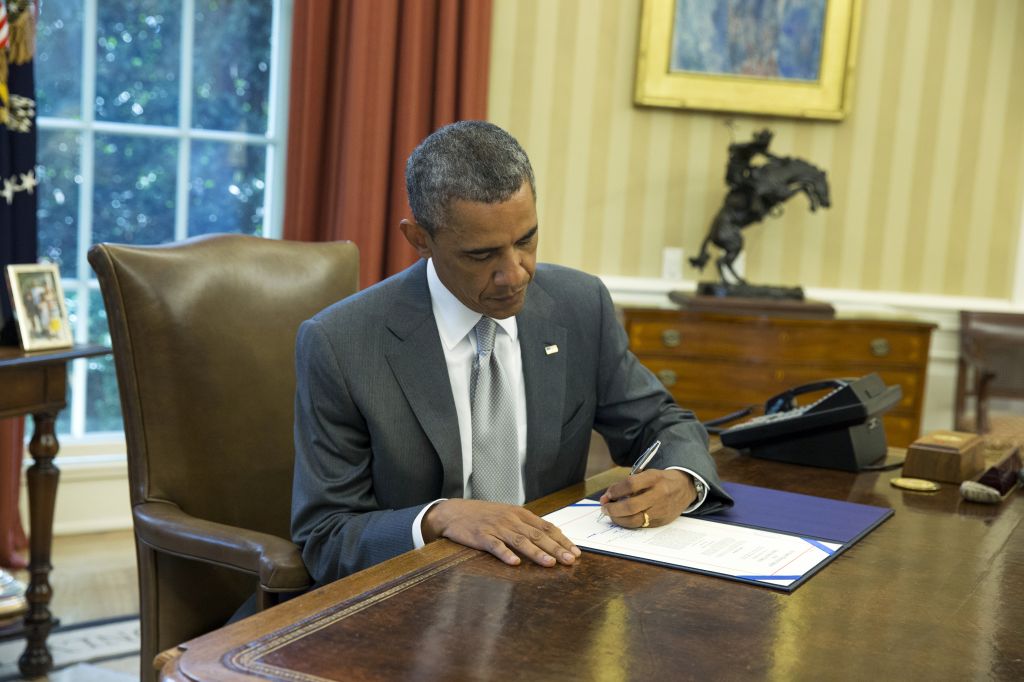

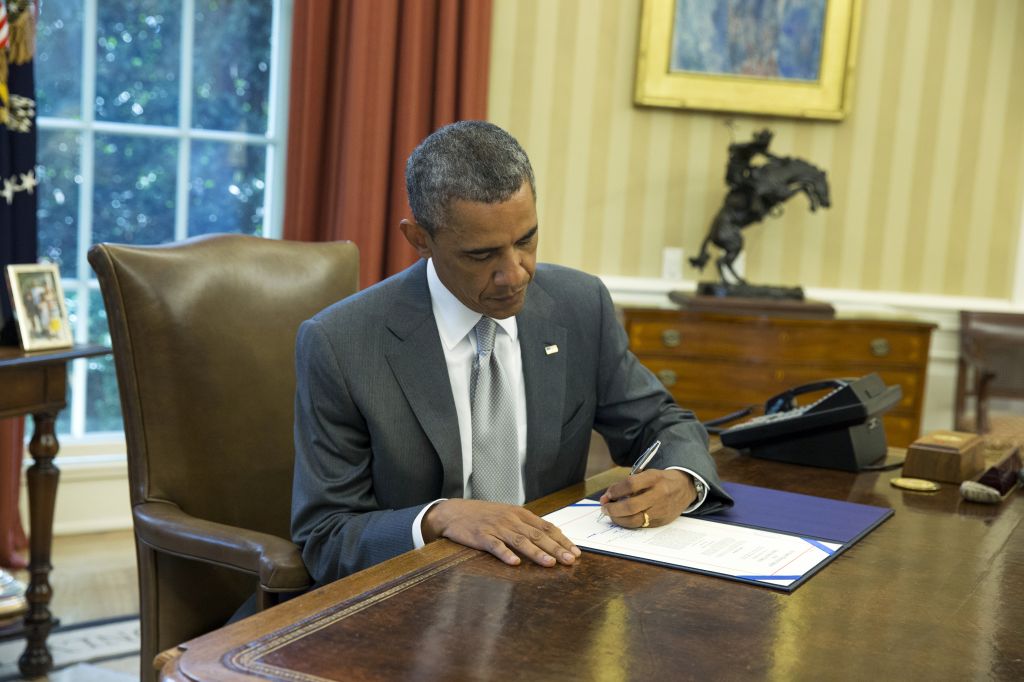

Obama approves $225 million in Iron Dome funding

Defense system has intercepted hundreds of rockets fired by Hamas toward residential neighborhoods in past month

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

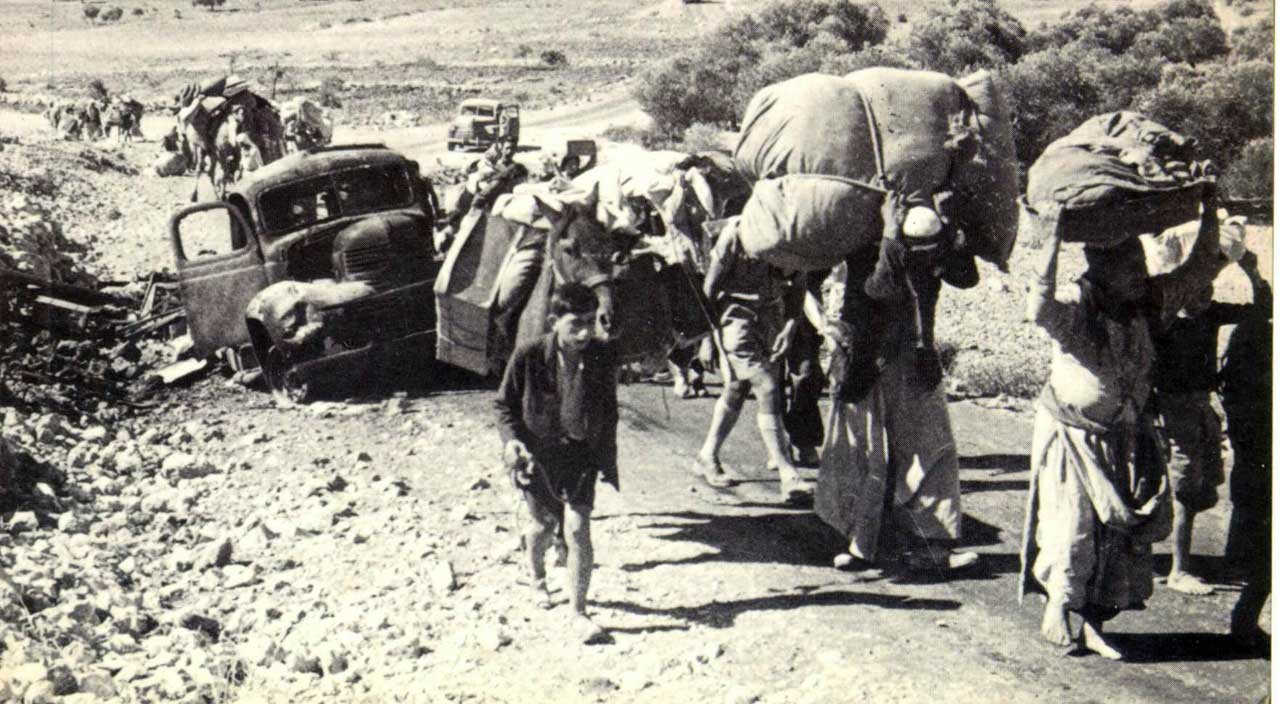

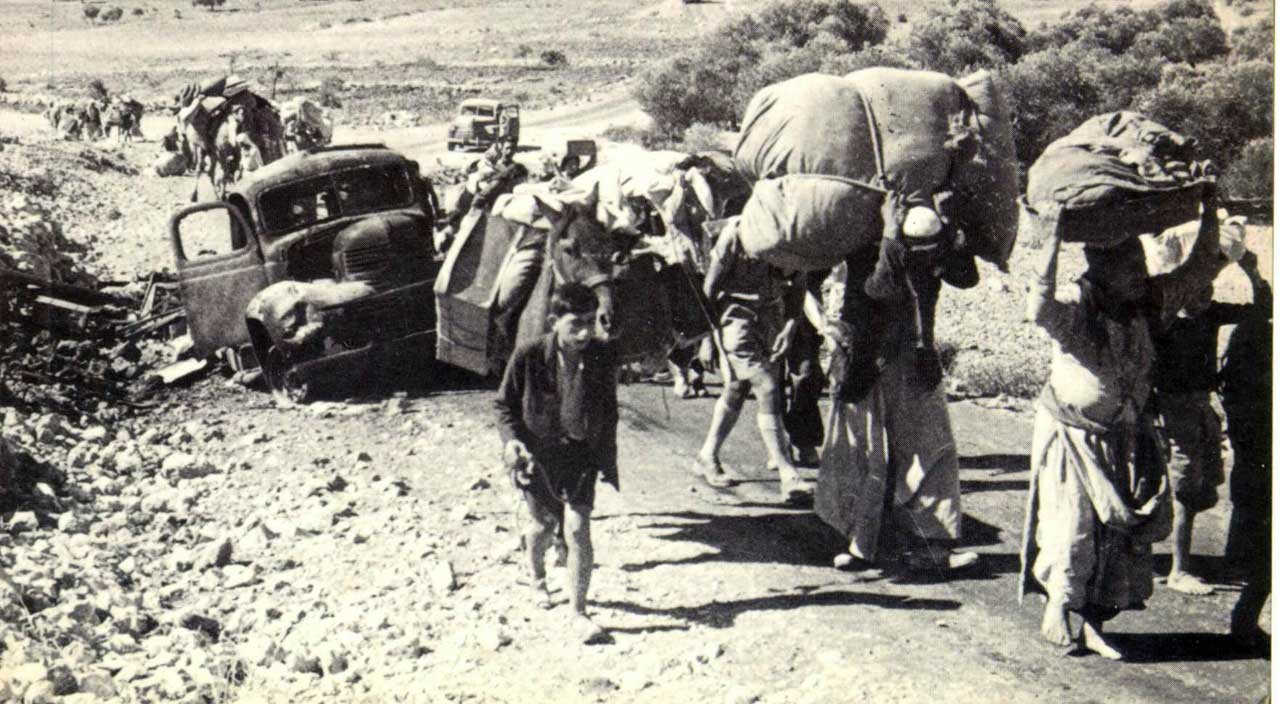

“determined that most of the Arabs in the country, over 400,000, were encouraged to leave or expelled in the first stage of the war—even before the Arab nations’ armies invaded.”